To survive, pathogens must shut down the host's defense mechanisms. One of these defense mechanisms comes from the mitochondria in the host's cell, which deprive the pathogens of the nutrients they need, limiting their growth. "We wanted to know how else mitochondrial behavior changes when mitochondria and pathogens encounter each other in the cell. Since the outer membrane of these organelles is the first point of contact with the invaders, we took a closer look at it," says study leader Dr. Lena Pernas of the Max Planck Institute for Biology of Aging.

Mitochondrien stoßen ihre „Haut“ ab

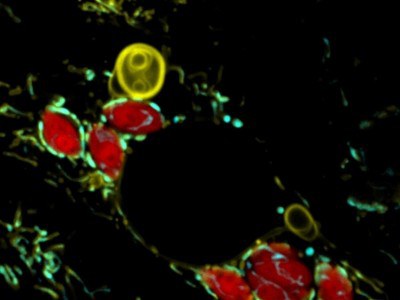

The researchers infected cells with the human parasite called Toxoplasma gondii and observed live under the microscope what happened to the mitochondria's outer membrane. "We saw that mitochondria that came into contact with the parasite detached large structures from their outer membrane. This was very puzzling to us. Why would mitochondria shed what is basically the link between them and the rest of the cell?" said Xianhe Li, first author of the study.

Hostile takeover

But how does the parasite get mitochondria to do that? The research team was able to show that the pathogen has a protein that mimics a mitochondrial host protein. It binds to a receptor on the outer membrane of mitochondria to gain access to the machinery that ensures proteins are imported into mitochondria. "In this way, the parasite hijacks a normal host response to mitochondrial stress. This leads to disarming of the mitochondria," says Pernas.

In a collaboration in Collaborative Research Center 1218 "Mitochondrial regulation of cellular function," Prof. Dr. Thomas Becker and Dr. Fabian den Brave from the Institute of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the University of Bonn investigated the influence of the parasitic protein on the uptake of proteins into the mitochondria. "We found with the help of the model organism baker's yeast that the binding of the protein to the receptor impairs protein uptake into the mitochondria," says Thomas Becker, a member of the Transdisciplinary Research Unit "Life and Health" at the University of Bonn.

"Other researchers have shown that a protein from the SARS-CoV-2 virus also binds to this transport receptor, suggesting that the receptor plays an important role in host-pathogen interactions," Pernas says. However, according to the researchers, further studies are needed to better understand its role in various infections.

Publication:

Xianhe Li, Julian Straub, Tânia Catarina Medeiros, Chahat Mehra, Fabian den Brave, Esra Peker, Ilian Atanassov, Katharina Stillger, Jonas Benjamin Michaelis, Emma Burbridge, Colin Adrain, Christian Münch, Jan Riemer, Thomas Becker, Lena F. Pernas: Mitochondrien geben ihre äußere Membran als Reaktion auf infektionsbedingten Stress ab. Wissenschaft; DOI: 10.1126/science.abi4343

CONTACT:

Prof. Dr. Thomas Becker

Institute for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

University Bonn

Tel: +49 228 73-2412

E-Mail: thbecker@uni-bonn.de

Corresponding author:

Dr. Lena Pernas

Max Planck Institute for Biology of Aging, Cologne, Germany

Tel.: +49 (0)221 379 70 770

E-Mail: LPernas@age.mpg.de